Béla Bartók: The Misfit Modernist Who Bridged Folk and Art

Among the "great five" composers of 20th-century music identified by Pierre Boulez—Stravinsky, Schoenberg, Berg, Webern, and Bartók—the Hungarian composer Béla Bartók stands apart as perhaps the most paradoxical figure. Throughout his life and even after his death, Bartók remained an anomaly, fitting uncomfortably into the rigid categories that defined his era's musical and political landscape.

A Life Shaped by History

Born in Hungary in 1881, Bartók lived through one of Europe's most turbulent periods, dying in American exile on September 26, 1945, just three weeks after World War II ended. His sense of isolation began early; at age 24, he prophetically wrote to his mother: "I know it, I can foretell it: this intellectual loneliness will be my fate."

This isolation stemmed partly from his unique position in the modernist movement. While his contemporaries like Schoenberg developed intellectually rigorous techniques such as the 12-tone system, Bartók brought what musicologist Richard Taruskin calls a "core of stubborn humanity" to his modernist innovations. His music refused the mathematical coldness often associated with avant-garde composition, maintaining a melodic warmth that connected high art with lived experience.

The Ethnomusicological Pioneer

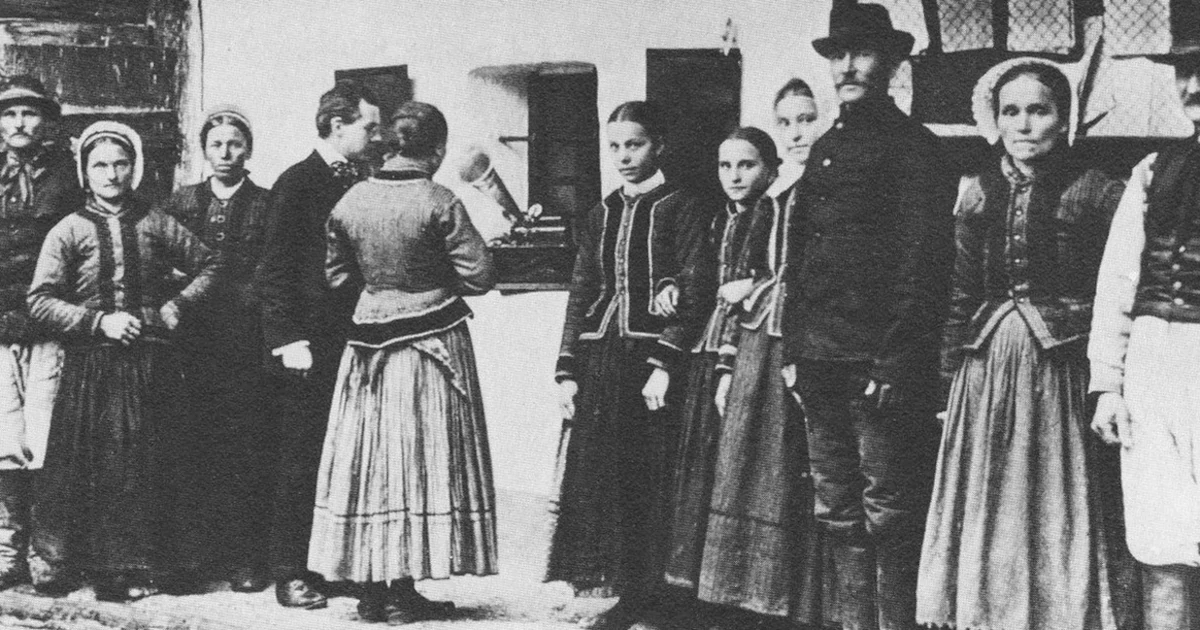

Bartók's defining moment came in 1904 when he heard a young Transylvanian nanny, Lidi Dósa, singing traditional Magyar folk songs. This encounter revealed that Hungarian peasant music was not, as commonly believed, a crude derivation of Romani music, but rather "a natural indigenous culture" with its own sophisticated traditions.

This discovery launched Bartók's lifelong project as an ethnomusicologist—a term that didn't even exist when he began his work. He traveled extensively throughout Hungary, Romania, Slovakia, Turkey, and North Africa, collecting and notating folk music. His resulting publications remain authoritative works on the subject.

These travels profoundly shaped Bartók's worldview, transforming his early Hungarian nationalism into what might be called humanistic internationalism. He discovered musical connections between Magyar traditions and those across Central Asia, Anatolia, and Siberia, noting that ordinary people showed little interest in national hostilities—a sentiment always driven by ruling classes rather than common folk.

Music as Lived Experience

For Bartók, folk music represented something beyond mere melody—it embodied what he called "the totality of lived experience." As he explained in 1928, truly understanding this music required direct contact with its sources: "In order to really feel the vitality of this music, one must, so to speak, have lived it—and this is only possible when one comes to know it through direct contact with the peasants."

This philosophy permeated his compositions, from the accessible Romanian Folk Dances to complex works like his String Quartet No. 5. Bartók saw no hierarchy between "high" and "low" musical aspirations, maintaining a democratic ear that valued the spiritual life present in all authentic musical expression.

Political Complexity and Anti-Fascist Stance

Bartók's politics defied easy categorization. He briefly participated in Béla Kun's Communist government in 1919, harbored early anti-Habsburg nationalist sentiments, and eventually sought refuge in capitalist America—yet he never joined any political party. Instead, he pursued what scholar Malcolm Gillies describes as "an individualistic vision of a spiritual commonality."

His anti-fascist convictions were unambiguous. By 1937, his hatred of Italian fascism was so intense he refused to visit the country. He banned performances of his work in Germany and, remarkably, was indignant when the Nazis excluded his music from their "degenerate art" exhibitions. When Hungarian "Jewish laws" were introduced in 1938, he joined non-Jewish intellectuals in protest, becoming so outspoken in his anti-Nazi stance that colleagues feared he would be among the first arrested by the Gestapo.

Exile and Legacy

At age 60, Bartók was forced to emigrate to America, exchanging a life of privilege for exile and poverty. In the United States, he was better known as a performer than a composer, struggling to make a living as a teacher and researcher before dying of leukemia in 1945.

The Cold War proved equally unkind to Bartók's reputation. His work was "ruthlessly partitioned, like Europe itself, into Eastern and Western zones." In Stalinist countries, his folk elements were praised while his modernist tendencies were viewed with suspicion. In the West, avant-garde critics misread his work as proto-serial while dismissing his more accessible pieces as compromises.

The Enduring Humanist

Perhaps Taruskin offers the most fitting assessment: "To leave Bartók out of the historical narrative means leaving out practically the only redeeming exception to the dismal saga of Modernist responses to barbarism." Bartók represents a unique figure who maintained artistic integrity while remaining connected to human experience, offering "a rebuke—and following rebuke, a possible redemption—to the sad history whereby over the course of the 20th century the autonomy of art has degenerated into irrelevance."

As Bartók foresaw, he remained a misfit throughout his life—too folksy for the avant-garde, too bourgeois for communists, too difficult for populists. Yet his music endures as the work of someone who never lost sight of the humanity he served: combining grace, joy, and dignity with an intelligence sharp enough to avoid sentimentality. In an age of ideological extremes, Bartók carved out a space for art that was both innovative and deeply human—a legacy that feels more relevant than ever in our own fractured times.

News,Latest news